Periods of equity market stress – risk or opportunity?

PERSPECTIVES | No. 33

- History shows that equity markets have always recovered after crises – and often gone on to reach new all-time highs.

- Well-timed investments during bear markets have historically delivered above-average returns.

- In times of high volatility and geopolitical shifts, broad diversification is key.

Equity markets regularly go through periods of significant strain and uncertainty. During such stress phases, prices fall sharply and sentiment tends to swing between fear and pessimism. For many investors, these periods appear primarily as a threat – concern over permanent losses often dominates decision-making. Most recently, erratic US trade policy has again triggered sharp market declines and elevated volatility. However, market downturns are not just a threat to wealth – they can also present opportunity. A look at the turbulent history of equity markets can help long-term investors put such phases into perspective. This article focuses on historical patterns using the US equity market as an example. Similar dynamics generally apply to global markets as well, although they have often shown slightly lower momentum and resilience in the past.

An overview of US market crashes

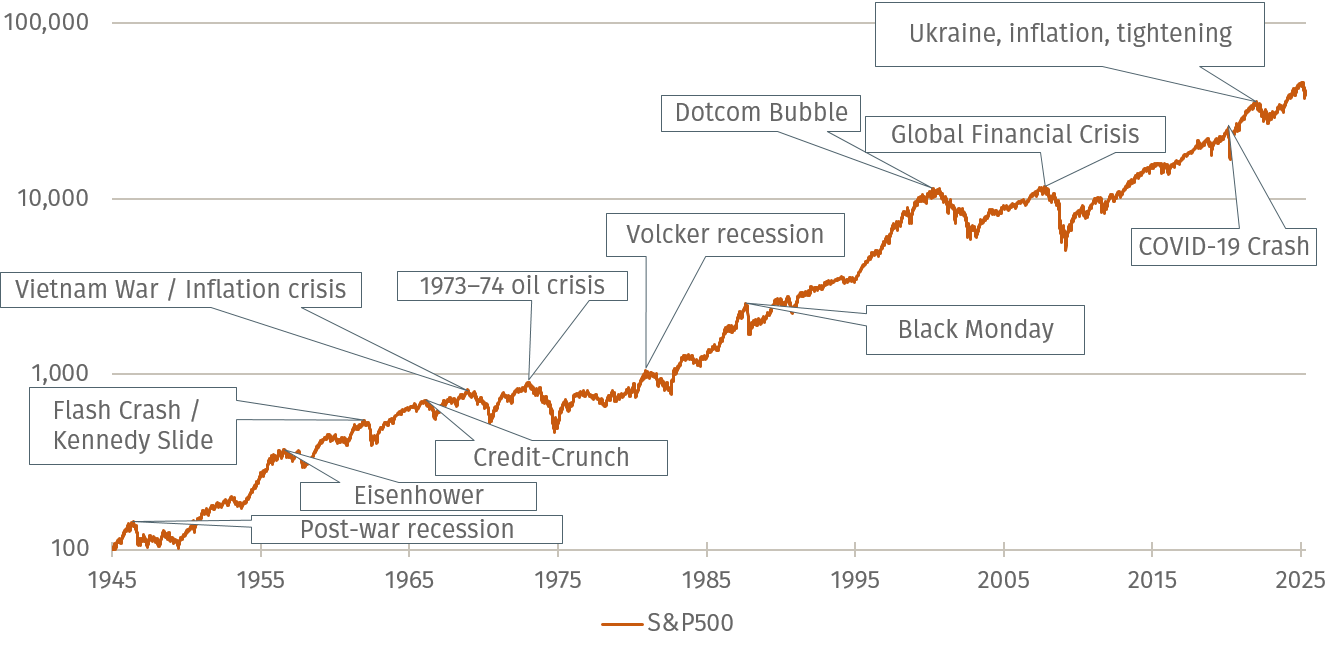

Since 1945, the United States has experienced twelve bear markets as measured by the S&P 500® – defined as declines of more than 20 percent. These downturns were typically triggered by real economic problems or external shocks that shook investor confidence. Bear markets often – though not always – coincided with recessions: falling corporate earnings and rising unemployment tended to dampen expectations for future economic growth. A textbook example is the oil crisis of 1973/74, when surging energy prices led to stagflation and the S&P 500® dropped by as much as 48 percent.

Monetary tightening has also repeatedly triggered significant market corrections. In the early 1980s, the determined rate-hiking cycle led by Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker – aimed at curbing runaway inflation – resulted in a recession and sharp equity market losses. A similar pattern emerged in 2022: fears over rising interest rates and an impending economic slowdown pushed US markets back into bear territory, with the S&P 500® falling by around 25 percent.

Figure 1: Historical trends and bear markets of the S&P 500® since 1945

1945 = 100, price index, logarithmic scale

In addition to cyclical fluctuations, structural imbalances and speculative bubbles can also trigger major market corrections. The bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000 is a striking example. After years of irrational exuberance in the technology sector, markets corrected sharply: between March 2000 and October 2002, the S&P 500® lost around 49 percent of its value, while the Nasdaq fell by approximately 78 percent. Just a few years later, the US housing crisis escalated into a global financial crisis. The collapse of the mortgage market and the resulting shockwaves in the banking sector triggered the most severe market downturn of the post-war period – with the S&P 500® dropping by around 57 percent between 2007 and 2009.

Finally, exogenous shocks such as wars, geopolitical tensions, trade conflicts or pandemics can trigger sudden market dislocations – even when underlying economic conditions previously appeared robust. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 led to a historic collapse: within just one month, the S&P 500® lost around 34 percent of its value – the fastest decline of that magnitude on record.

Drivers of recovery

As varied as the causes and trajectories of major market crises may have been, a recurring pattern emerges: after each significant correction, equity markets have so far fully recovered and eventually reached new all-time highs. But what explains this remarkable resilience?

One of the key drivers lies in economic fundamentals. Recessions and crises regularly trigger adjustment processes that, over time, have a stabilising effect. Fiscal stimulus and accommodative monetary policy play a crucial role in this context. Governments typically respond with investment programmes and fiscal incentives, while central banks support the economy through interest rate cuts and liquidity injections. For instance, the massive interventions by central banks and governments following the global financial crisis laid the foundation for a prolonged economic recovery. Similarly, in response to the COVID-19 shock, monetary and fiscal measures of unprecedented scale were implemented within a very short period – resulting in a strong rebound in global economic activity (and, as is well known, inflation) as early as the following year. Major crises also often lead to tighter regulation. After the global financial crisis, for example, capital and liquidity requirements for banks were significantly strengthened worldwide – a step that has improved the resilience of the financial system and reinforced investor confidence over the long term.

Market corrections also often lead to a revaluation of companies. Excesses are unwound, fundamental risks are repriced more accurately, and inefficient business models tend to disappear. In contrast, innovative companies often emerge stronger from crises. After the bursting of the dot-com bubble, for instance, successful technology firms established themselves in the more disciplined post-crisis environment—many of which are now global market leaders.

In addition to fundamental factors, market psychology plays a crucial role. After periods of extreme uncertainty, sentiment can shift rapidly. As fear subsides and initial price recoveries take hold, many investors re-enter the market. Combined with confidence in supportive central bank policy, this can generate positive momentum that further accelerates the recovery.

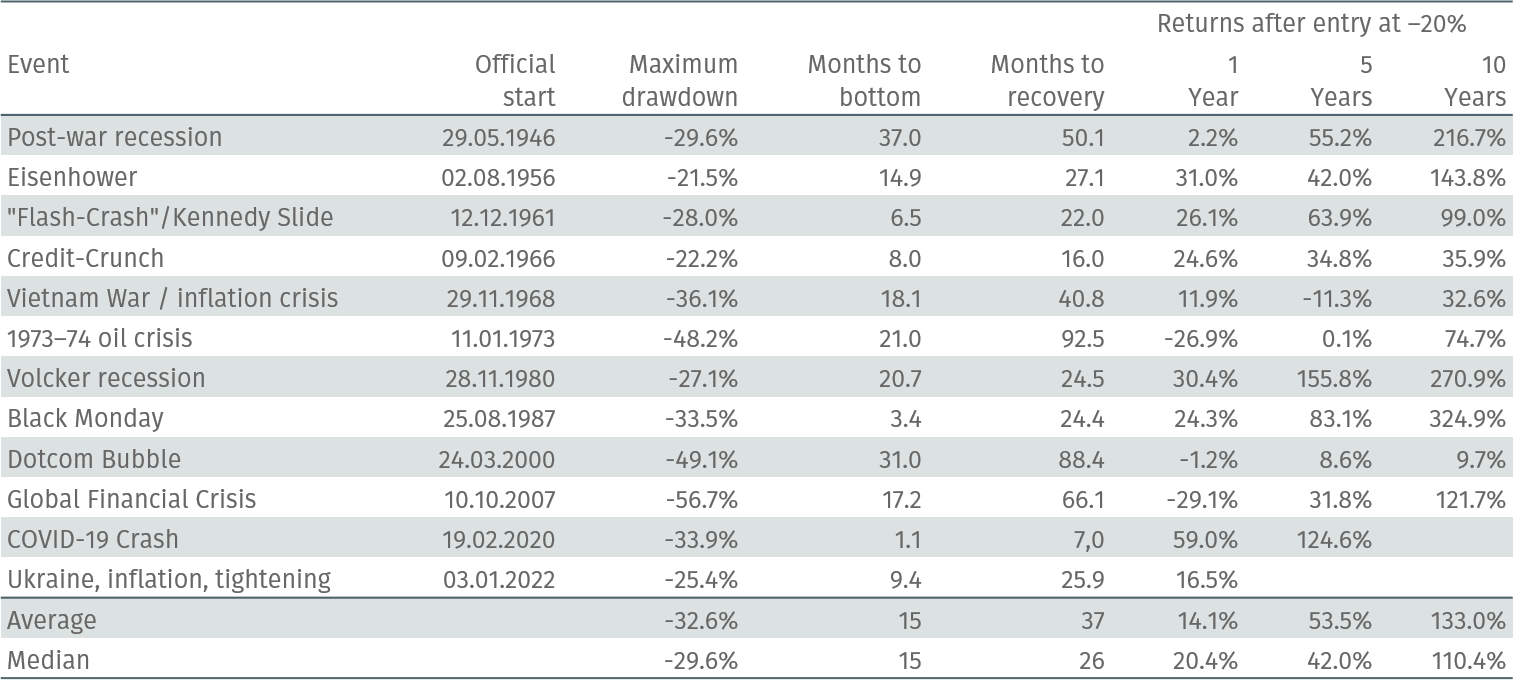

A statistical perspective

A look at the historical development of bear markets, as shown in Table 1, highlights the long-term resilience of equity markets. While the duration of recoveries following major downturns varies considerably – from the COVID-19 crash in 2020, where index levels recovered within just seven months, to the 1973/74 oil crisis, after which it took around seven and a half years to return to pre-crisis levels—markets have historically regained lost ground more quickly in most cases. On a median basis, severe declines were typically recouped within two to three years.

Table 1: Periods of market stress in the US since 1945, S&P 500®

Price index excluding dividends

What stands out is the performance following significant market declines. Investors who entered the S&P 500® during periods of severe dislocation – specifically in a bear market after a drop of more than 20 percent – have historically achieved above-average returns. On average, one year after such entry points, returns were around 14 percent; after five years, +53 percent; and after ten years, as much as +133 percent – all figures excluding dividends. For comparison: the S&P 500® has delivered average annual growth of 8 percent since 1945.

For the investor

What lessons can investors draw from history in the current environment? First, external shocks – such as recent US trade policies – do not derail equity markets over the long term. While global power structures and supply chains are likely to shift going forward, companies are capable of adapting. Moreover, even US economic policy is ultimately subject to market discipline. The suspension of many tariffs in response to sharply rising US Treasury yields is an early indication of that adjustment. Second, crises are part of the nature of equity markets. They help clear out inefficiencies and can foster innovation and renewal among companies. Third, stress phases can offer attractive entry points for investors seeking to achieve above-average long-term returns. That said, it is important to acknowledge that interim losses during such phases can be substantial, and some crises may take years to play out. This makes it all the more important for investors to align their investment strategy with their individual risk–return profile. Long-term investors with a higher risk tolerance can use periods of heightened volatility strategically, while more conservative investors may benefit from broad diversification. Active diversification across asset classes remains the most effective way to manage drawdowns and volatility.

This article first appeared on 13 May 2025 on the Börsen-Zeitung website.