Twin deficits in the US: More than just a cosmetic flaw?

PERSPECTIVES | No. 34

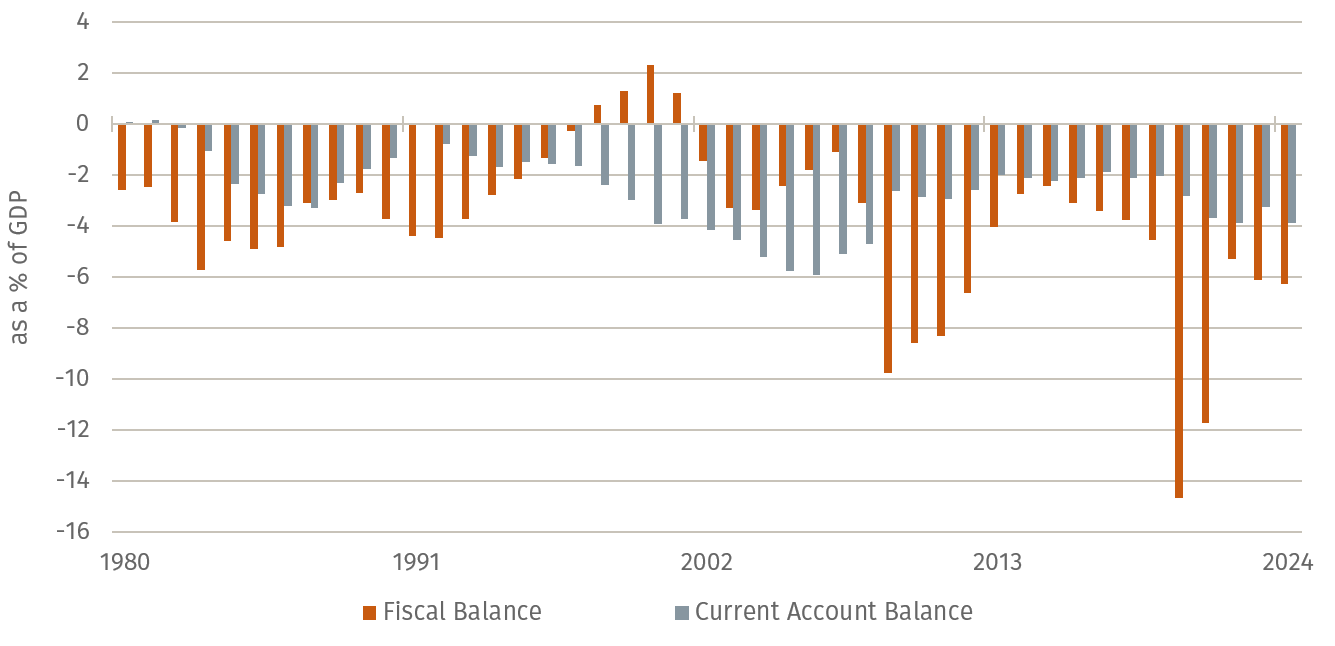

- The simultaneous occurrence of fiscal and current account deficits is a structural feature of the U.S. economy.

- However, the current mix of rising interest burdens, expansive fiscal policy, and growing protectionism marks a new dimension.

- For globally diversified investors, a nuanced view of U.S. fiscal sustainability and currency risks is essential to remain agile amid potential market shifts.

The U.S. financial markets dominate the global financial system. With a market capitalisation of USD 59 trillion, U.S. equities account for approximately 63% of global free-float equity markets, while U.S. bonds, at USD 58 trillion, represent around 40% of the global bond market. U.S. equity markets are nearly six times larger than their European counterparts, and the bond markets roughly twice as large. Adding to this dominance is the U.S. dollar's role as the world’s primary reserve currency – around 58% of global central bank reserves are held in dollars.

The depth and liquidity of US financial markets have allowed the country to finance significant fiscal and current account deficits simultaneously for decades. The so called "twin deficit," referring to both a budget and current account deficit, has long been a structural feature of the US economy. Investors traditionally viewed this as a minor blemish with little impact on the appeal of the United States. However, a substantial shift in sentiment is now emerging. On one hand, the US fiscal position is steadily deteriorating, on the other, the Trump administration's protectionist approach to reducing the trade deficit is increasingly unsettling markets.

High interest burden reduces fiscal flexibility

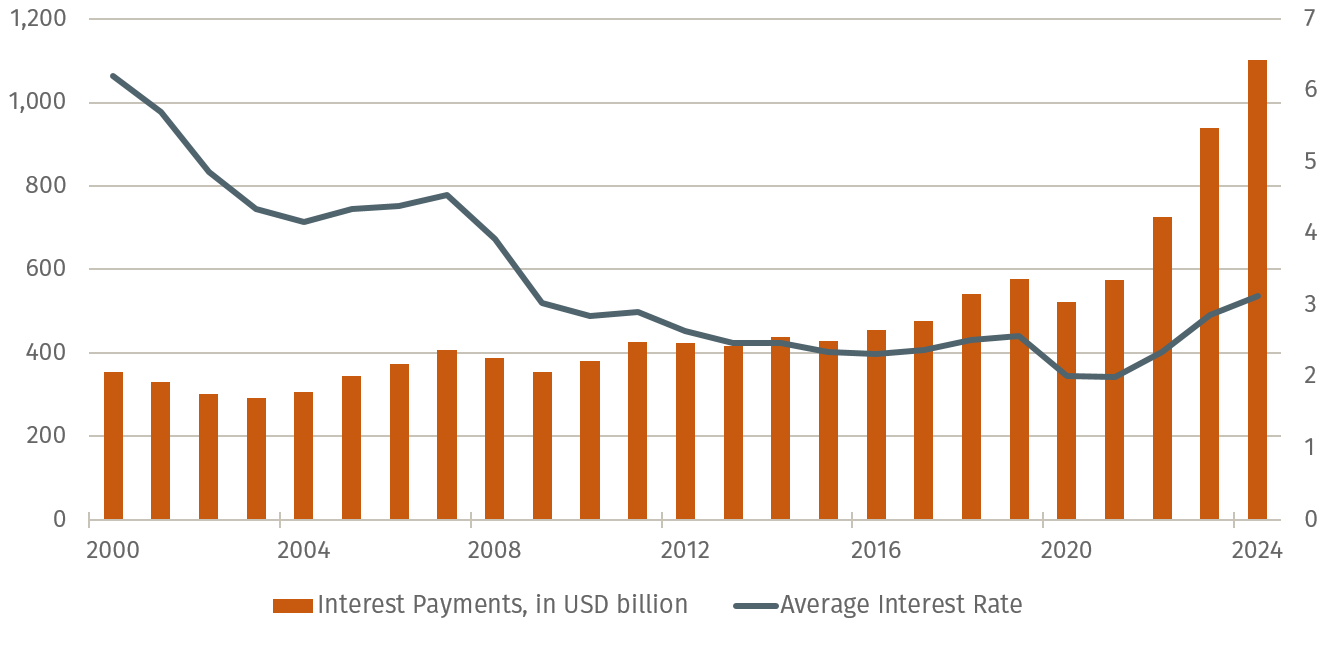

U.S. government debt currently stands at around 120% of GDP – an historically elevated level. At the same time, the significantly tighter monetary policy since 2022 and the higher interest rate environment have led to a marked increase in financing costs. The average interest rate on U.S. government debt, which typically lags market developments, has now reached 3% – roughly one percentage point higher than in 2020. With total debt exceeding USD 36 trillion, this rise represents a substantial burden. In just three years, annual interest payments have doubled, now amounting to approximately USD 1.1 trillion – more than current U.S. defence spending, which stands just below USD 1 trillion. The rapid increase in debt-servicing costs is thus significantly constraining the government's fiscal flexibility.

Figure 2: Interest payments are becoming an increasing burden

Average interest rate as a ratio of interest payments to total debt

The expansive fiscal policies under Donald Trump have further exacerbated the situation. The recently passed tax package – the "Big Beautiful Bill" – is expected to increase government debt by an additional USD 3 trillion over the next decade, potentially pushing the annual deficit above 7% of GDP. This raises the risk of a debt spiral, where new borrowing is required solely to service existing debt. Long-term fiscal stability in the United States could be seriously threatened, especially if interest rates continue to rise.

U.S. tariff policies weigh on consumers and investment

Alongside expansive fiscal policy, the U.S. president has sought to reduce the current account deficit through tariffs. Nearly all imports have been subject to tariffs aimed at shrinking the trade deficit and boosting domestic industry. The expectation is that American companies will produce more, earn more, and create new jobs. However, this is only part of the picture. For consumers, tariffs act like a consumption tax, making goods more expensive and reducing purchasing power. Yale University’s "Budget Lab" estimates that tariffs will raise prices by 1.5% in 2025, effectively cutting the real purchasing power of American households by an average of USD 2,000. Moreover, the unclear direction of trade and fiscal policies, alongside frequent tariff announcements and delays, significantly disrupt corporate investment planning. Companies face heightened uncertainty, complicating or even deterring long-term investment decisions. As a result, much-needed investments may be delayed or abandoned, ultimately undermining the competitiveness and growth potential of the U.S. economy.

Conflict between trade and fiscal policy

Furthermore, it is questionable whether expansive fiscal policy can be reconciled with a protectionist trade strategy. Large budget deficits typically boost domestic demand, either through direct public investment or tax cuts encouraging higher consumption and investment by households and businesses. However, if sufficient domestic production capacity cannot be expanded in the short term – which appears challenging in the U.S. given the tight labour market, already high capacity utilisation, and decades of established global supply chains – then the additional demand will have to be met through imports.

This inevitably leads to a larger current account deficit. The macroeconomic identity – that the difference between domestic savings and investment equals the current account balance – remains fully valid. Therefore, a rising fiscal deficit combined with stable or declining private savings will inevitably result in a growing current account deficit. This development becomes particularly concerning when fiscal measures are consumption-driven rather than productivity-enhancing.

The U.S. government’s policies thus create a fundamental conflict: while trade barriers aim to protect domestic companies, expansive fiscal measures simultaneously drive import demand, exacerbating the current account deficit. This inherent contradiction could undermine the credibility and effectiveness of U.S. economic policy in the long term, increasing the risk of macroeconomic instability.

For capital market investors

The U.S. twin deficit is not a new phenomenon, but the combination of rising debt servicing costs, expansive fiscal policy, and increasing protectionism represents a new challenge. In the short term, the depth of U.S. capital markets is likely to continue attracting inflows. However, over the long term, international investors' willingness to finance the deficit may wane – potentially impacting the U.S. dollar and bond market risk premiums. The sharp depreciation of the dollar alongside 10-year Treasury yields above 4% since the start of the year could be an early indicator. For globally diversified investors, a nuanced assessment of U.S. fiscal sustainability and currency risks remains essential. Equally important is maintaining portfolio flexibility in terms of duration and currency allocation to respond swiftly to evolving market conditions.